Shipping Containers: Types, Sizes, Uses, and Buying Tips

Shipping containers sit at the crossroads of global logistics and local problem-solving. They’re rugged, standardized steel boxes that enable efficient trade, but they’ve also become a flexible building block for storage, pop-up structures, and modular construction. Understanding how they are built, sized, and graded—and how to evaluate them—helps you make smarter choices whether you’re moving goods, adding secure on-site storage, or exploring container-based spaces.

Outline:

– Types and construction: key container categories, materials, strengths, and trade-offs.

– Sizes and specifications: standard dimensions, weight ratings, and standards that matter.

– Logistics and lifecycle: how containers move, age, and are maintained.

– Alternative uses and modifications: real-world applications and design considerations.

– Buying tips, pricing, and conclusion: inspection checklists, cost drivers, delivery, and a practical wrap-up.

Types and Construction: What These Steel Boxes Are Made Of—and Why It Matters

Containers look simple at a glance, but their design is the product of decades of refinement. Most general-purpose units—often called dry vans—are made from weathering steel (commonly known as Corten) that forms a stable oxide layer, slowing corrosion. Corrugated side walls give strength with relatively thin panels, while the frame, corner posts, and corner castings carry stacking loads and interface with cranes and chassis through twistlocks. Floors are typically marine-grade plywood or bamboo/composite boards supported by steel cross members. Doors at one end are gasketed, with locking bars and cam keepers to achieve a wind-and-watertight seal when properly maintained.

Beyond the familiar dry van, specialized types expand capabilities:

– High-cube: About one foot taller, enabling greater internal volume and more headroom for shelving or conversion projects.

– Open-top: A removable tarpaulin and roof bows allow loading of tall cargo from above; useful for machinery and irregular items.

– Flat rack: Collapsible end walls and no side walls for oversized cargo; ideal for machinery, pipes, and vehicles.

– Double-door and side-opening: Access from both ends or a full side, speeding loading and making storage retrieval easier.

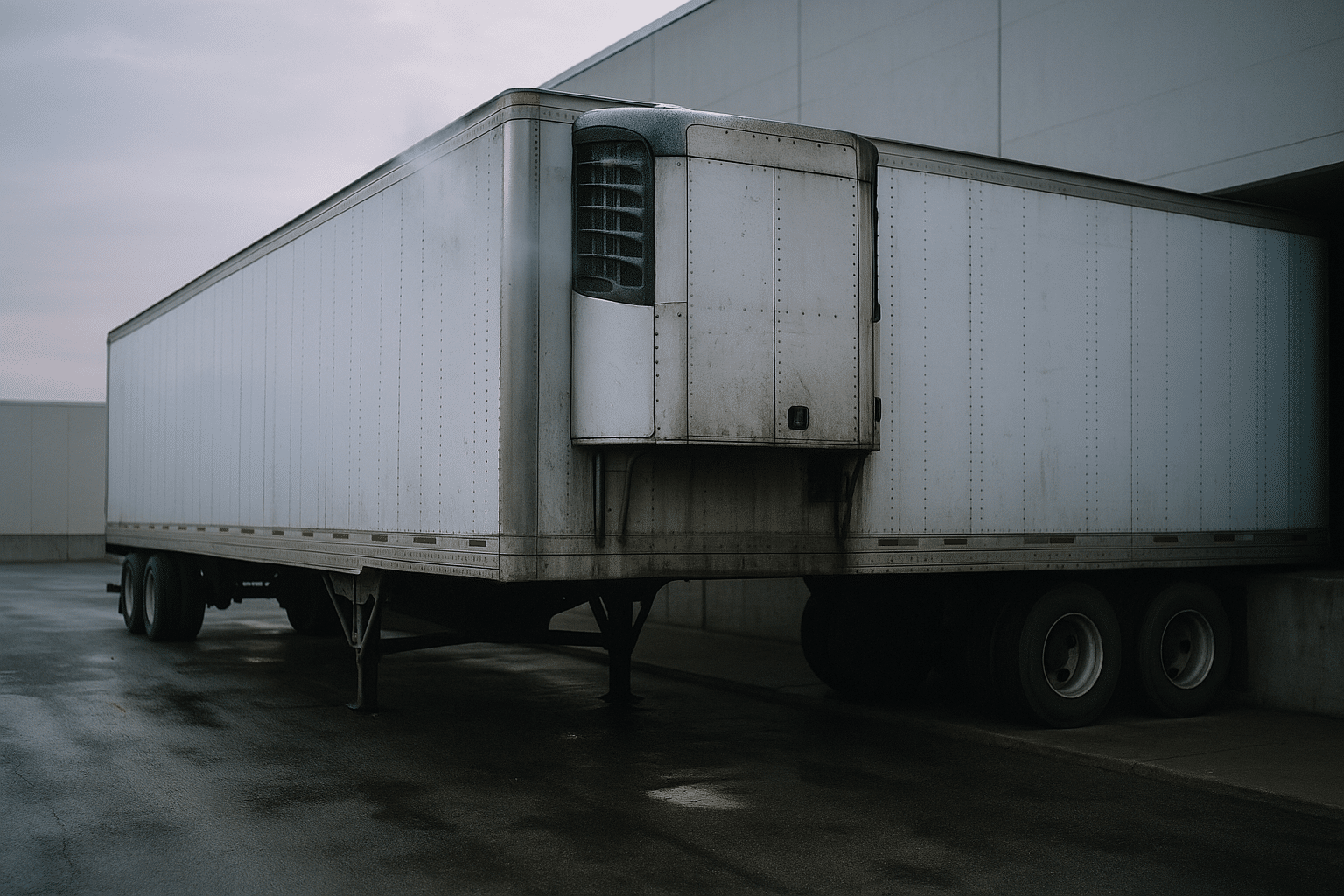

– Refrigerated (reefer): Insulated walls with an integrated unit to maintain temperatures typically from well below freezing to cool ranges; common in perishables.

– Tank: A cylindrical tank within a frame for liquids or powders, built to stringent standards for pressure and safety.

– Ventilated and bulk: Designed for commodities needing airflow or top-loading bulk handling.

Each type involves trade-offs. For example, open-tops simplify loading but reduce security and weather resistance compared to a sealed roof. Flat racks carry awkward cargo but offer minimal protection, relying on securement and tarping. Reefers provide precise temperature control but are heavier and costlier to operate and maintain. When choosing, think about both immediate needs and likely repurposing. A high-cube dry container is a versatile option if you imagine future shelving, mezzanines, or a conversion. For storage, double-door units can streamline access, while side-opening designs shine in retail or workshop setups. The materials and standardized details—the corner castings, fork pockets, and uniform rail heights—are what let containers stack nine high on ships yet also sit neatly on a backyard pad. That duality—massive strength packaged in a modular format—is why containers remain a disciplined, dependable solution across industries.

Standard Sizes and Specifications: Dimensions, Ratings, and the Numbers That Count

Standardization is the superpower of shipping containers. Most general-purpose units follow ISO 668, which sets the sizes and fitting locations so they can be handled by the same equipment worldwide. The two most common footprints are nominal 20-foot and 40-foot lengths, with widths around 8 feet (approximately 2.438 m). Heights come in standard (about 8 ft 6 in or 2.591 m) and high-cube (about 9 ft 6 in or 2.896 m).

Typical figures, which vary slightly by manufacturer, provide a practical sense of capacity:

– 20 ft dry (standard height): External 6.06 m L x 2.44 m W x 2.59 m H; internal length near 5.9 m; internal width about 2.35 m; internal height about 2.39 m; volume roughly 33 m³. Tare mass commonly ~2,000–2,300 kg; maximum gross mass often up to 30,480 kg.

– 40 ft dry (standard height): External 12.19 m L x 2.44 m W x 2.59 m H; internal volume ~67 m³. Tare ~3,600–3,900 kg; maximum gross mass often around 30,480 kg.

– 40 ft high-cube: External height ~2.90 m; internal volume ~76 m³. Slightly higher tare due to taller panels.

Beyond size, key specs influence safe use:

– Corner casting geometry: Ensures twistlock compatibility across ships, trains, and trucks.

– Racking and stacking strength: Corner posts are tested to withstand stacked loads well above in-service weights, with test values often exceeding 190,000 kg in combined stacking load scenarios.

– Floor ratings: Cross members and deck boards are designed for forklift axle loads; check the plate for limits if you run heavy equipment inside.

– CSC plate and ACEP markings: Proof the container meets the International Convention for Safe Containers requirements for ongoing inspection.

In practice, the “TEU” (twenty-foot equivalent unit) is the basic measure of capacity in shipping. A 40-foot container counts as 2 TEU, and the global equipment pool runs into the tens of millions of TEU, enabling dense, predictable freight flows. For buyers and builders, specifications translate into real decisions: a 20-foot unit is compact and easier to site, while a 40-foot high-cube maximizes cubic space for shelving, insulation, or tall equipment. Always verify the actual internal dimensions if you have tight clearances; even small differences in door opening height can affect machinery moves. Finally, remember that published ratings assume the container is in sound condition—damaged frames, corroded corner posts, or compromised floors can reduce safe capacity and should be flagged during inspection.

Logistics and Lifecycle: How Containers Move, Age, and Stay Useful

From ship to rail to truck, containers live an intermodal life. They are lifted by spreader beams engaging corner castings, locked onto ship cell guides, secured to rail well cars, and attached to chassis with twistlocks. This choreography works because every handling point is standardized. After years in circulation, units accumulate dings, weld repairs, and layers of paint. Salt spray and abrasion do their slow work, and operators manage the fleet through depots where repairs, repainting, and safety inspections occur. The CSC framework mandates periodic checks so boxes remain safe for stacking and sea voyages.

Lifecycle patterns depend on routes and cargo. Reefers typically have higher maintenance demands due to their machinery, while dry vans may run for a decade or more in international service before being retired to domestic use or sold for storage. Environmental conditions matter: tropical humidity and coastal air accelerate corrosion; frequent rail moves can add impact stress. Common aging issues include:

– Corrosion at door sills, roof seams, and underfloor cross members where standing water lingers.

– Door alignment problems caused by frame racking impacts or worn hinges.

– Degraded rubber gaskets leading to leaks and drafts.

– Floor delamination or soft spots from heavy forklift traffic or spills.

Condensation—sometimes called “container rain”—is a practical concern in many climates. Warm, moist air cooled by a night drop can condense on steel ceilings and drip. Mitigations include:

– Passive vents and larger louvered openings positioned high on side walls.

– Desiccant packs for sensitive goods.

– Interior linings, spray foam, or insulated panels to raise interior surface temperatures.

– Continuous low-level airflow using solar vents where power is limited.

Sustainability is an additional motivation to extend container life. Reusing an existing steel shell for storage or as part of a modular structure reduces demand for new steel and the associated embodied carbon. That said, responsible reuse includes safe modifications: cutting large openings changes load paths; removing a portion of a corrugated wall reduces racking resistance. Good practice involves reinforcing cut edges with rectangular tubing, maintaining load transfer around doors and windows, and consulting local codes for wind, snow, and seismic requirements. With care, a container can transition from global traveler to dependable on-site asset, continuing to deliver value well beyond its ocean-going years.

Alternative Uses and Modifications: From Secure Storage to Modular Spaces

Containers found fame as sturdy storage units, but their modular structure invites creativity. For storage, their appeal is straightforward: lockable steel doors, weather resistance, and a predictable footprint that can be delivered quickly. Beyond storage, containers underpin pop-up retail, site offices, workshops, laboratories, and even community facilities. Their rhythm of corrugations and industrial patina can read as honest and modern when handled thoughtfully.

Successful conversions start with planning. Consider how people and equipment move through the space, where daylight should enter, and how to handle temperature and moisture. Key design considerations include:

– Openings: Cutouts for doors and windows require structural framing to maintain racking resistance.

– Insulation: Closed-cell spray foam offers good vapor control and high R-value per inch; rigid mineral wool or polyiso panels can also perform well when detailed with continuous air and vapor control layers.

– Condensation control: A continuous air barrier and thermal break reduce cold bridging; vented rainscreens behind cladding help in humid climates.

– Electrical and fire safety: Use conduit or protected cavities; follow local codes for egress, smoke detection, and ratings.

– Foundations: Simple concrete pads, strip footings, or steel piers level the unit and keep steel off wet ground; anchor for wind where required.

For workshops and offices, side openings or full-length doors can transform a narrow box into an engaging facade with flexible display or service areas. Linking two containers with a central infill space yields a wider plan while preserving modular efficiency. High-cube units add headroom for duct runs or mezzanines. Exterior cladding—wood, fiber-cement, corrugated metal—can soften the industrial look while creating a cavity for insulation and wiring. Inside, durable finishes like plywood, cement board, or steel studs with gypsum form robust walls, and careful detailing at the floor edges addresses thermal bridging.

Even when you’re not building habitable spaces, a few simple upgrades improve day-to-day use:

– LED strip lighting with motion sensors powered by a small solar kit for off-grid storage.

– Anti-condensation roof coatings or insulated liners in climates with big temperature swings.

– Shelving systems bolted to existing lashing rings to avoid penetrating the shell.

– Security features such as lock boxes that shield padlocks and tamper indicators on hasps.

The through-line is pragmatic creativity. Containers are not magic shortcuts, but they are a reliable, modular chassis. When you respect their structural logic and the realities of weather and codes, they can become hardworking spaces that feel intentional rather than improvised.

Buying Tips, Pricing, Delivery, and Conclusion: A Practical Path for Owners and Builders

Buying a container is part engineering decision, part logistics puzzle. Start by matching the grade to your purpose:

– New/one-trip: Shipped once from the factory, typically very clean with minimal wear; priced higher but with long service life potential.

– Cargo-worthy: Inspected and certified for international shipping; a solid option if you might ship or want higher structural assurance.

– Wind and watertight (WWT): Doors seal, no visible holes; widely used for storage. Not necessarily certified for sea.

– As-is: Cheapest, but may have structural issues, leaks, or contamination risks; inspect carefully.

Inspection is where value is made or lost. Bring a flashlight and look beyond the paint:

– Exterior: Check roof for soft spots and ponding rust; inspect corner posts and bottom rails for corrosion or bent steel.

– Doors: Ensure both leaves swing freely; examine gaskets, cams, and keepers; confirm the locking bars rotate smoothly.

– Floor: Look for delamination, dark staining, or screw pull-out; tap with a hammer for hollow sounds over weak spots.

– Interior: Close the doors in daylight to spot pinhole leaks; sniff for chemical odors that may signal contamination.

– Documentation: Verify the CSC plate info, serial number, and any repair records or survey reports.

Pricing fluctuates with global trade imbalances, steel costs, and shipping demand. In some regions, 20-foot WWT units may range from the low thousands to several thousand in local currency, while 40-foot high-cubes typically command a higher premium. Specialized types like reefers, open-tops, or side-openers cost more due to added features or lower supply. Delivery can be a substantial share of the total: tilt-bed trucks or crane services charge by distance, difficulty, and time on site. Ask for all-in quotes that include offloading, and confirm site access—tight turns, overhead lines, soft ground, and slope all complicate placements.

Prepare your site before delivery. A level, compacted base with timber sleepers or concrete pads helps keep the frame square and the doors aligned. Plan the container’s orientation so prevailing winds don’t blow rain into the doors, and so drainage runs away from the sills. If the unit will become a permanent structure, check local permitting and zoning early; adding utilities, cladding, or signage may trigger code requirements. For security, consider a lock box and high-quality padlock, and record the container’s ID for insurance.

Conclusion: For logistics managers, small business owners, builders, and tinkerers, containers are a pragmatic tool—durable, modular, and widely available. Choose a type and size that truly fits the job, verify specifications against your loading and clearance needs, and inspect with a skeptical eye. Budget for delivery and site prep, not just the box. With these steps, you turn a steel rectangle into a dependable asset that works hard on day one and keeps paying you back for years to come.